When comparing power outputs across different terrain types, the influence of course profiles on pedaling patterns becomes clear.

So Why Does Zero Watts Matters?

First of all, when analyzing power data, it’s important to note that average power calculations typically include zero watts, while cadence data excludes zeroes by default.

Understanding why cyclists experience “zero watts” moments during races is crucial for race strategy.

On flat terrain, brief periods of coasting are valuable for conserving energy, while uphill sections leave less room for rest. Riders can maximize their efficiency by leveraging flat course drafting opportunities to reduce their workload and save their strength for the more demanding moments, such as climbs or sprint finishes.

Therefore, reading power data post-race highlights the distinct strategies used in different terrains, helping cyclists optimize their performance.

One of the quickest ways to improve your technical skills and reduce unnecessary pedaling is by participating in group rides with stronger or more experienced cyclists. These riders often have a wealth of knowledge on drafting, positioning, and conserving energy.

Don’t hesitate to ask them for advice during or after rides, and make a conscious effort to observe how they move within the peloton, handle surges, and conserve energy.

By sharpening your technical skills in this way, you’ll better utilize coasting opportunities in races and preserve more energy for critical moments.

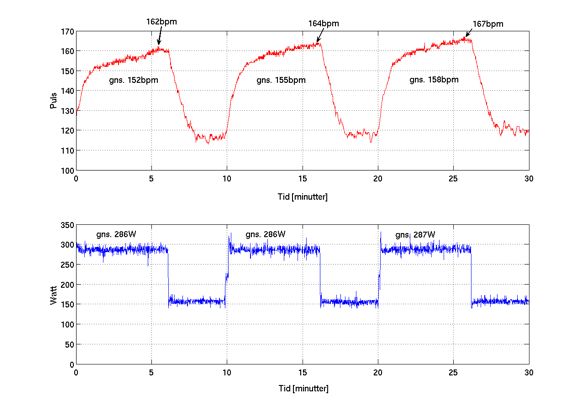

Uphill Terrain: Consistent Power and Controlled Intervals

Uphill terrain offers cyclists a unique opportunity for more controlled and steady power outputs, making it easier to perform structured power meter-based intervals.

The resistance from the gradient naturally stabilizes pedaling, reducing the tendency to coast and creating a more even power profile compared to flat terrain.

This makes long climbs (e.g., 15-20 minutes) ideal for specific sub-threshold or threshold intervals, where maintaining consistent power is critical.

Using Climbs for Interval Training:

On hills, riders can focus on maintaining a targeted power output over longer durations without the distractions present on flat roads. This steady effort helps develop aerobic endurance and power at threshold, critical for sustained efforts during races.

Long, steady intervals are easier to control on climbs, making it easier to focus on power targets, cadence, and overall pacing. Uphill riding forces riders to stay on the pedals, delivering a more consistent effort compared to the power variability seen on flat terrain.

However, it’s important to note that relying solely on uphill intervals can lead to imbalances in training. The power profile and cadence while climbing are different from what riders experience on flat terrain.

On a climb, cadence typically drops due to the increased resistance, and the effort feels more sustained. On flat terrain, cadence tends to be higher, and power output is more variable due to microadjustments, drafting, and wind effects.

Balancing Your Training:

Therefore, while climbs offer an excellent opportunity for structured power training, it’s crucial to balance this with flat-road intervals to reflect the diverse demands of race day.

Doing all intervals on climbs can result in slower cadence habits and difficulty adapting to the fluctuations in power needed on flat terrain or during group racing.

A mixed approach, incorporating both uphill and flat terrain intervals, ensures that cyclists can handle a wide variety of race scenarios.

Flat Terrain: Power Variability and Training Adaptations

Flat terrain, while seemingly less demanding than climbs, presents its own unique set of challenges that require specific training adaptations.

Most races feature long stretches of flat or near-flat terrain, meaning cyclists spend significant time in fluctuating power zones.

On these flat sections, riders often alternate between short bursts of power and coasting, particularly in group settings where drafting and wind management are essential.

In races, the ability to ride efficiently on flat terrain is crucial. Drafting allows riders to conserve energy, but it also requires them to react to frequent surges and speed changes within the peloton.

This makes flat races more tactical, with riders constantly adjusting their position and reacting to sudden accelerations, often resulting in brief moments of zero watts as they coast and conserve energy for critical moments.

These energy-saving microadjustments are essential for lasting through the race and performing optimally in key segments like breakaways, sprints, or uphill attacks.

Training for Flat Terrain Power Surges:

Given the frequent power fluctuations on flat roads, training should incorporate more than just steady-state efforts.

To replicate race conditions, it’s essential to perform race-like intervals, including bursts of high power followed by coasting or low-intensity pedaling.

For example, riders can use varied VO2 max intervals where they alternate between short, intense efforts (such as 30 seconds at 150% FTP) and recovery periods. This type of training simulates the power profile of racing, helping cyclists better handle the unpredictability of surges and efforts demanded on flat terrain.

Additionally, endurance and efficiency on flat terrain require a rider to optimize their ability to conserve energy in groups, draft effectively, and prepare for moments when power spikes are needed.

Focusing on skills like paceline riding, responding to attacks, and hndling surges in training will make riders better equipped for race day.

Why Flat Terrain Skills Matter:

Neglecting the skills needed for flat terrain could put a rider at a disadvantage, especially since a large portion of many races is spent on these roads.

By focusing on a combination of power output stability and short, race-like bursts, cyclists can improve their ability to conserve energy, handle race dynamics, and perform consistently well on flat courses.

What you should do:

I suggest you should start keeping track of your “zero power” moments during your upcoming races. While it’s not a perfect metric to assess your overall effort, simply being aware of this number can help you make smarter decisions during the race.

Monitoring it can guide you to conserve energy more effectively, allowing you to save your legs for the final critical moments of the race, such as climbs, breakaways, or sprint finishes. This small adjustment can have a big impact on your race outcomes.

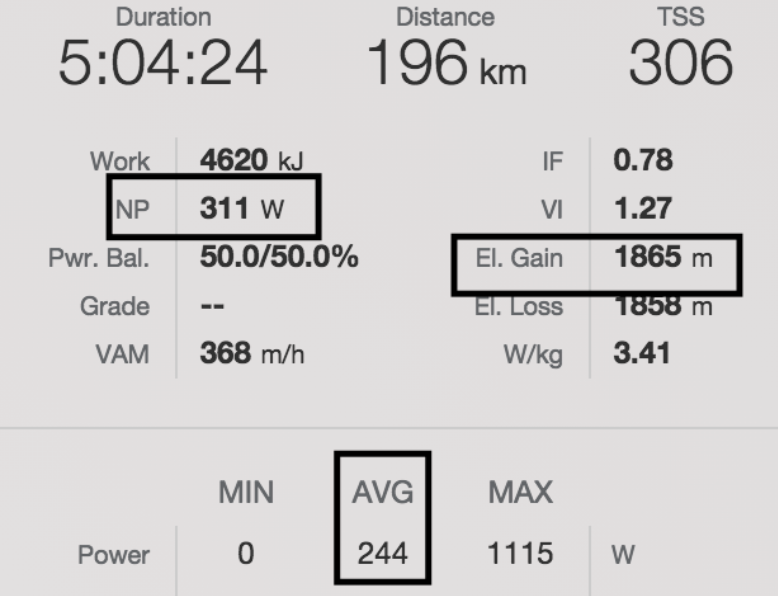

Comparing Normalized Power vs. Average Power in Race Scenarios

In races with highly variable power outputs, using normalized power is often a helpful metric for understanding the demands on your body.

Normalized power is a mathematically weighted version of average power, designed to estimate what your average power would have been if the ride had been steady, without zeroes.

Average Power includes all values, from surges to coasting, giving a raw figure that doesn’t account for fluctuations or energy spikes.

Normalized Power, however, adjusts for variability, reflecting the physiological stress as if you had ridden at a constant effort.

When analyzing race data, comparing normalized power (NP) and average power (AP) provides valuable insights into your performance.

Normalized power provides a more accurate reflection of the physiological cost of riding a course with fluctuating efforts, allowing you to better assess your performance and energy expenditure during inconsistent race scenarios.

In races with significant power fluctuations—due to drafting, surges, or terrain—Normalized power offers a more accurate reflection of the actual effort your body endured.

For example, a race with heavy surges might show a low average power but a much higher normalized power, revealing how physically demanding the race really was despite periods of coasting or recovery.

Tracking both metrics helps riders better understand the true demands of a race, and adjust training to improve energy management and consistency under race conditions.

Unpredictable Efforts: Training for Explosive Race Situations

Cycling races are often unpredictable, with sudden surges and explosive efforts required at key moments. These bursts of power can be the difference between staying in the lead group or getting dropped.

To effectively handle these situations, it’s essential to train for the unpredictability of racing by incorporating a wide range of intervals. By simulating the random presentation of hard efforts, you can better prepare your body for the dynamic nature of race-day efforts.

Instead of focusing on a single magic interval or intensity, consider training across a broad spectrum of intervals, for example:

Power Sprints (10 seconds at maximum effort):

These short, explosive bursts mirror the surges seen in breakaways as they enter a tactical phase. Incorporating sprints into your training can sharpen your anaerobic power, essential for responding quickly to attacks or accelerations in the peloton.

Also, it’s worth to notice that power sprints are the closest you can get to strength training on your bike.

Anaerobic endurance (20 seconds to 1 minute): These intervals target your ability to sustain high power outputs over brief periods, similar to the sharp efforts needed during steep climbs or attacks. You can alternate these bursts with coasting or low-intensity recovery to mimic race situations.

When training for a road cycling event, it is important to focus on both aerobic exercise and anaerobic processes. While most of the work is done aerobically, anaerobic power is still essential for making attacks and dropping other riders.

It is clear that aerobic exercise should always be your main priority, however, never underestimate the value of performing an anaerobic workout as part of your race preparation.

VO2 max (2 to 5 minutes at VO2 max – or slightly lower): These efforts simulate the sustained pulls you might need to bridge gaps, chase down breakaways, or push hard over a climb. Incorporating longer, high-intensity intervals helps build the endurance required for prolonged efforts in races.

By using this varied approach to interval training, you’ll train your body to handle the unpredictable demands of racing.

Regular exposure to these types of efforts will also build mental resilience, as you become more accustomed to digging deep at unpredictable moments. This broad base of training will help you be ready for any race scenario—whether it’s a short, sharp climb or a long, grinding attack.

Ultimately, the key is not to overcomplicate your training with endless metrics but to focus on a well-rounded plan that includes consistent volume, regular intervals, and attention to race-specific scenarios.

There’s no single interval session that will prepare you for every aspect of racing, but by building a comprehensive approach, you’ll have the fitness and versatility needed to respond to whatever race day throws your way.

If you want to read more about how to optimize your cycling performance with data insights, please take a look at my recent book.

Order your copy here: